Le DIORAMA

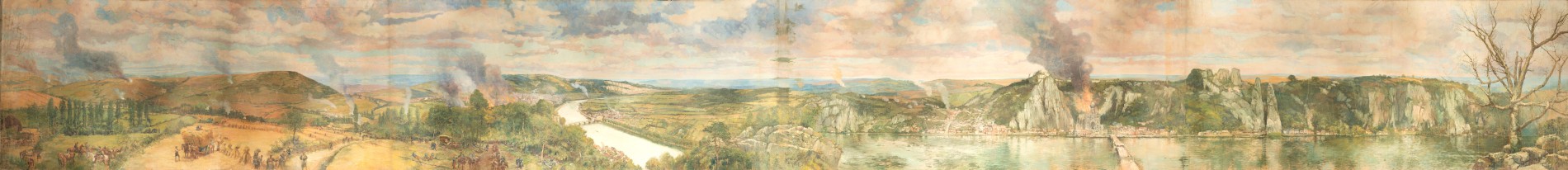

Peinture sur toile – 8 mètres / 72 mètres – 1937 – Alfred Bastien

C’est un cri d’alarme que pousse Alfred Bastien, inquiet de la montée en puissance du nazisme dans le nouveau Reich allemand.

Œuvre longtemps oubliée, le Diorama des Batailles de la Meuse offre au spectateur une vue plongeante sur la vallée de la Meuse telle qu’on peut l’admirer depuis la rive gauche du fleuve (Ouest).

Le tableau est divisé en scènes qui, chacune, évoque un moment de ces semaines tragiques de l’agression allemande sur la Belgique neutre d’août et septembre 1914.

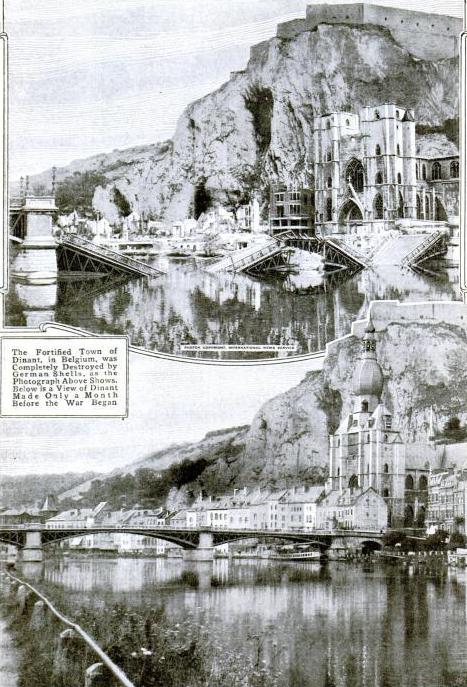

Des moissons de l’été sur la gauche à l’évocation des destructions de Namur et de Dinant jusqu’à l’arbre mort, symbole des victimes de la guerre, à droite du tableau, c’est l’Histoire que donne à voir ce Diorama.

Et c’est aussi un cri d’alarme.

Inaugurée en 1937, le Diorama des Batailles de la Meuse veut alerter le spectateur.

À nouveau, la guerre est proche…

Le DIORAMA

Découvrez les principales scènes de l’œuvre d’Alfred Bastien en cliquant sur les zones interactives.

Vous pouvez aussi zoomer ou naviguer latéralement pour visualiser l’ensemble de la toile.

Dans les détails

Pour comprendre le sens des scènes principales du Diorama, mises en perspective, expliquées et illustrées

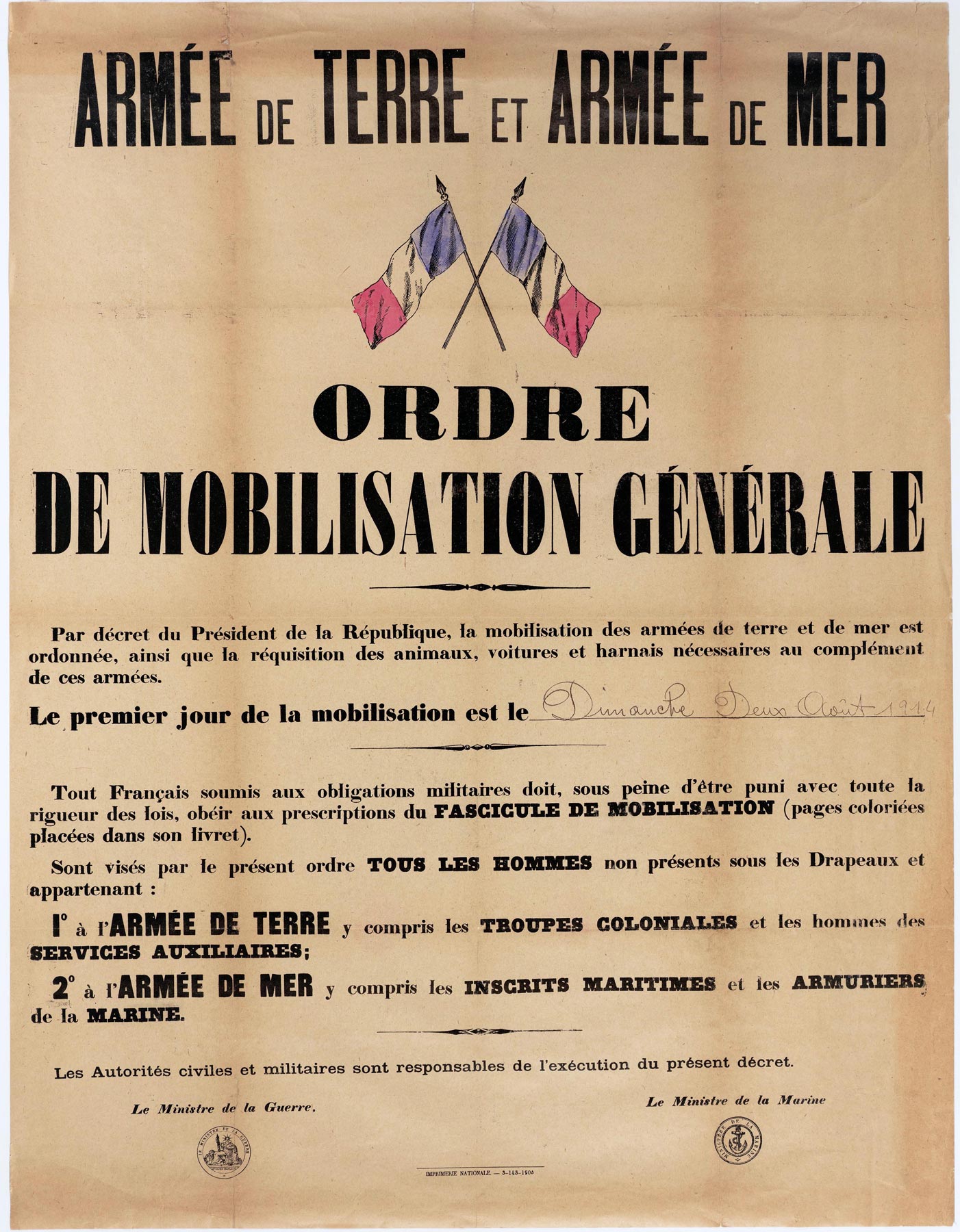

La mobilisation

À Liège, début août 1914 : l'armée belge est mobilisée

L'invasion

Les Allemands foulent le sol liégeois

La résistance liégeoise

Les exactions allemandes s’enchaînent dans la Province de Liège

L'aviation

Une colombe tout sauf pacifique dans le ciel liégeois

La résistance namuroise

Namur s’apprête à l'entrée en guerre

À l'heure Allemande

Les ennemis occupent la ville dès la fin du mois

L'occupation

La ville de Namur accuse de nombreux dégâts

La P.F.N.

La Position Fortifiée de Namur capitule

La Croix-Rouge

Le rôle de la Croix-Rouge belge lors des combats

Le pont de Jambes

Le génie belge détruit le pont de Jambes

Dans la Province

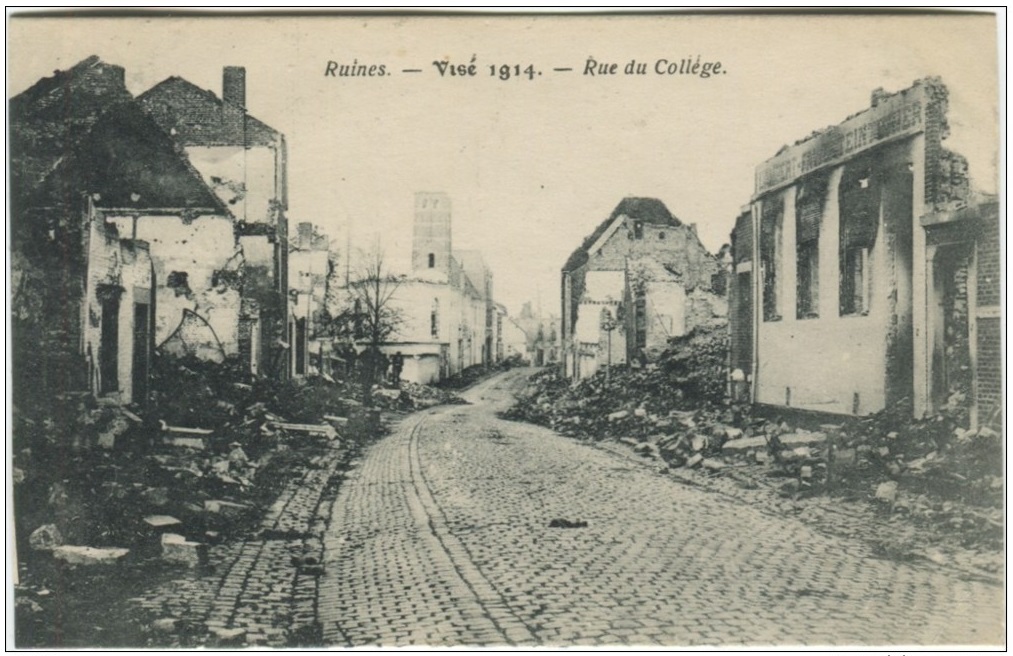

Au tour de la Province de Namur de subir les exactions allemandes

Vers Dinant

Les Allemands marquent leur passage vers Dinant d’autres atrocités

Les massacres

Quand les Allemands débarquent dans la vallée mosane

Le 15 août

Le 15 août à Dinant : récit d’une longue journée

Le 23 août

Les Dinantais décomptent leurs morts

La collégiale

La collégiale de Dinant vit sa énième restauration

Affrontements sur la Meuse

Les Allemands marquent leur présence ans la vallée mosane

Les petits quartiers

La fureur allemande n’épargne pas les petits quartiers

La nature

Les arbres : témoins, mutilés et symboles de la guerre

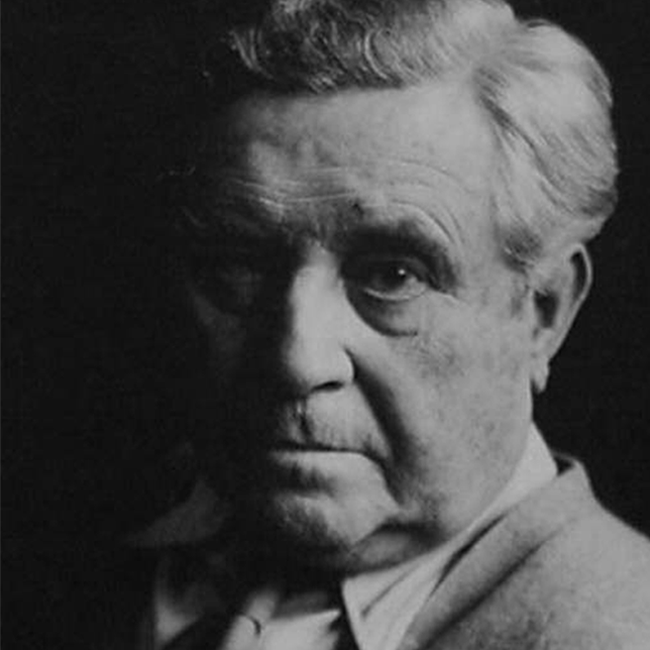

Alfred BASTIEN, le peintre

Alfred BASTIEN (1873 – 1955) est l’un des grands maîtres belges des dioramas et panoramas mais il s’est aussi fait connaître pour son abondante production de peintures de chevalet.

Alfred BASTIEN

Né en 1873 à Ixelles, Alfred BASTIEN est le huitième enfant d'une famille modeste. Frappé très jeune par les décès prématurés de sa soeur, de son frère et de sa mère, il quitte la maison familiale pour étudier à l'Académie des Beaux-Arts de Gand, puis à l'Académie des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles.

Alfred Bastien

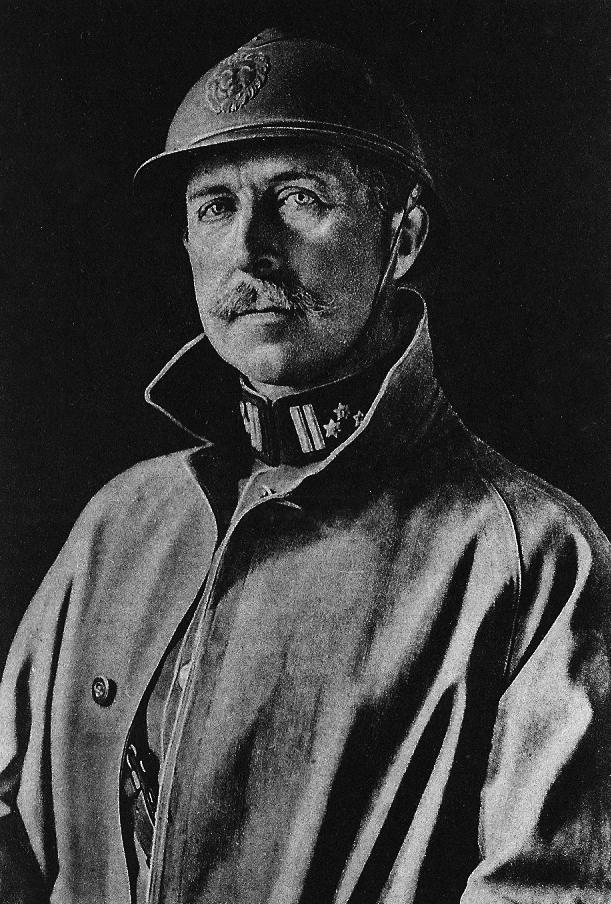

En octobre 1914, quelques semaines après le début du conflit, il s'exile en Angleterre puis il s'engage comme volontaire de guerre en 1915.

Il est incorporé en 1916 au sein de la section artistique de l'armée

belge puis détaché, en 1918, auprès de l'armée canadienne. Pendant ces longs mois, il peint

de nombreuses scènes de la guerre, tant en Belgique qu'en France. Depuis cette période,

l'artiste a de bons contacts avec la famille royale qu'il a rencontrée à plusieurs reprises.

Tout au long de son existence, Alfred BASTIEN s'est efforcé de partager sa passion pour

l'art et la peinture, en tant que professeur puis comme Directeur de l'Académie royale des

Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles, notamment.

Pacifiste convaincu, il s'est aussi fait connaitre pour ses engagements politiques, en

particulier au sein du Parti Communiste belge.

Il meurt le 7 juin 1955.

ALFRED BASTIEN - Juin 1918

Esquisse au crayon du major Georges P.Vanier

Bibliothèque et Archives Canada / Creative Commons

HISTOIRE DES PANORMAS ET DIORAMAS

Immenses toiles illustrant des paysages parfois animés de scènes

historiques, les panoramas et les dioramas constituent une forme artistique spectaculaire et

immersive qui a eu son âge d'or au XIXème sicle et au début du XXème. Techniquement, les

panoramas se distinguent des dioramas en ce que les premiers offrent au spectateur une vue à

360° tandis que les seconds sont des toiles planes ou légèrement cintrées.

Inventé en 1787 par le peintre écossais Robert BARKER, le panorama est donc un vaste

tableau circulaire exposé dans une rotonde de sorte que le regarde du visiteur qui le

découvre depuis une plateforme située en son centre embrasse l'ensemble de l'oeuvre tout

autour de lui.

Le sentiment de trompe-l'oeil est encore renforcé par une lumière zénitable cachée du

spectateur par un velum.

Rober BARKER, 1787, le premier panorama /Creative Commons

Photo : Ferditje / Creative Commons

HISTOIRE DES PANORAMAS ET DIORAMAS (suite)

Souvent enrichi par des éléments positionnés en avant-plan de l’œuvre

(des personnages, des objets, des plantes, des décors peints, etc.), le panorama (et donc

aussi le diorama) vise à créer l’illusion de se retrouver au cœur même de l’action ou du

paysage représenté.

Véritables ancêtres du cinéma tant par les dimensions des œuvres que par le souci des

artistes de plonger le spectateur dans une histoire ou un décor dépaysant, le panorama et le

diorama ont rencontré très vite un fort succès en Europe et en Amérique du Nord. Les

premiers prenaient généralement pour décor des paysages panoramiques urbains permettant aux

spectateurs de découvrir des villes étrangères ou idéalisées.

Puis, à partir du XIXème siècle, les sujets se diversifient. Le thème de la guerre est

repris par plusieurs artistes, souvent dans le cadre d’approches propagandistes pour les

nations européennes. L’exotisme rencontre lui aussi l’intérêt du public. C’est l’âge d’or du

colonialisme et les spectateurs européens se pressent pour découvrir des paysages d’Afrique

et de la lointaine Amérique.

L’essor du cinéma dans l’entre-deux guerres signera la déchéance progressive de cette forme

artistique qui fut longtemps très populaire et qui connaît aujourd’hui un regain d’intérêt

chez de nombreux créateurs de par le monde.

Franz ROUBAUD - Panorama de la Bataille de Borodino de 1812

Photo : Dennis Jarvis / Creative Commons

LE DIORAMA D'ALFRED BASTIEN

L'APPROCHE PICTURALE

Monumentale, la toile d’Alfred BASTIEN offre une vue plongeante

sur les rives de la Meuse. A l’extrême gauche, se déploie le pays de Liège avec ses collines

et ses places fortes. Puis, c’est la défense tragique de Namur et de ses environs : la

ville, incendiée en plusieurs lieux, apparaît en flammes à l’arrière-plan tandis qu’on

aperçoit au premier plan les troupes belges et françaises qui quittent Namur et amorcent la

retraite sur ordre du général Michel.

L’œuvre est véritablement un récit, une histoire qui se lit du regard et qui donne à voir

les premiers jours de l’invasion allemande, de l’insouciance des moissons jusqu’au triste

spectacle de l’arbre mort qui annonce la terrible hécatombe.

LE DIORAMA D'ALFRED BASTIEN

APPROCHE PICTURALE (suite)

De près, le coup de pinceau paraît relativement grossier mais

l’œuvre doit être contemplée d’une certaine distance comme devaient l’être tous les dioramas

et panoramas.

Effectivement, en reculant de quelques pas, le spectateur découvre à quel point Alfred

BASTIEN domine parfaitement sa technique picturale.

La profondeur de champ, entre l’arc de la Meuse, les collines au loin et cet arbre mort qui

trône seul de ce côté du fleuve donne au spectateur l’impression qu’il s’approche pour

contempler sur l’autre rive un spectacle de désolation.

En approchant son regard de la toile, la maîtrise technique de l’artiste apparaît

clairement, notamment dans le geste adopté pour peindre les éléments, l’eau, la terre et le

ciel. Les fumées qui s’élèvent des collines donnent l’impression de se perdre dans le ciel

tourmenté tandis qu’aux pieds de la Citadelle de Dinant, les flammes qui ravagent la

collégiale se reflètent dans les flots de la Meuse.

En opposant le spectacle grandiose de la nature aux désastres causés par la guerre et les

hommes, Alfred BASTIEN nous donne à réfléchir, à méditer sur les conséquences de nos

pulsions destructrices.

Clairement, cette œuvre est un message.

LES AUTRES OEUVRES DE L'ARTISTE

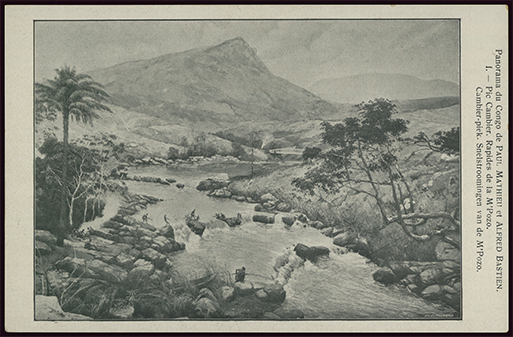

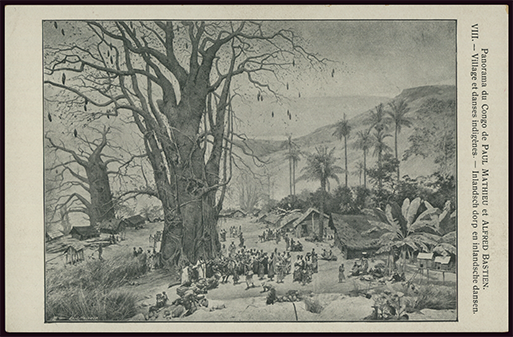

Après ses années d’études à Gand, Bruxelles et Paris où il copie les maîtres anciens, se passionne pour le romantisme de Delacroix et le réalisme de Courbet et subit l’influence des impressionnistes, Alfred BASTIEN entreprend de longs voyages en Europe, en Afrique du Nord, au Congo belge, en Inde, au Japon, en Chine et dans les îles du Pacifique sud.

Ghent University Library - Creative Commons

En 1911, à la demande du Roi Albert, le gouvernement belge lui commande, ainsi qu’à Paul Mathieu, le Panorama du Congo destiné à être présenté à l’Exposition universelle et internationale de Gand de 1913. Illustrant la colonie sous ses aspects les plus divers, l’œuvre aux couleurs chatoyantes rencontre un énorme succès.

Ghent University Library - Creative Commons

LES AUTRES OEUVRES DE L'ARTISTE (suite)

Pendant la guerre, en tant qu’artiste officiel de l'armée belge

et, pendant quelques mois, comme artiste missionné auprès de l’armée canadienne, Alfred

Bastien réalise certaines de ses plus belles œuvres, comme autant de témoignages de la

réalité du conflit sur les fronts de Belgique et de France.

Hormis sa production de guerre, Bastien est un peintre fécond qui produit un nombre

incalculable de peintures de chevalet illustrant des paysages, des natures mortes, des

scènes figurées et des portraits.

ALFRED BASTIEN - Canadian Cavalry Ready in a Wood

Canadian

War Museum / Public domain

LES AUTRES OEUVRES DE L'ARTISTE (suite)

En 1919 et 1920, il peint avec Charly Léonard et Charles Swyncop le Panorama de la bataille de l'Yser de 1914 qui donne à voir l’une des batailles clés du début de la guerre, avec son cortège de victimes et de destructions.

LE PANORMA DE L'YSER - 1920

Séquence d'actualité sur la

visite du Ministre de la Défense belge à l'exposition du peintre Bastien (1873-1955).

Cinémathèque

Royale de Belgique - EFG - The European Film Gateway / Domaine Public

Panorama de la bataille de l'Yser

Extrait - Incendie des

halles d'Ypres

LES ÉCRITS D'ALFRED BASTIEN

Le peintre est aussi un lecteur infatigable et un écrivain prolixe.

Sa vie durant, il confie, dans ses carnets personnels, ses réflexions sur la vie politique,

quotidienne et artistique de son temps.

Parallèlement, il entretient une correspondance abondante avec de nombreuses personnalités.

Ses écrits révèlent l’importance que prenait le diorama des Batailles de la Meuse aux yeux

de l’artiste.

15 novembre 1935

"J'ai commencé la première esquisse de la Meuse en 1914."

Novembre 1935

"Les rochers de Freyr... de Courbet dont la liquidité de la Meuse me

poursuivra toujours.

Ah le grand bon frère !

14 février 1936

« Le contrat pour le Panorama des batailles de Meuse en 1914 va passer chez le notaire. Il sera placé à Namur et décidera très probablement d’un grand changement dans notre vie : le rêve de la petite maison en Ardenne, près de la Meuse, dans les bois… se réalisera-t-il…ce serait trop beau ! Incha Allah ! »

22 avril 1936

« Bonne journée. Le ciel est entamé, les horizons bleus, très fins, très lointains…les chevaux se groupent. La main revient. Il y a déjà quarante mètres de fait. Chaque panneau – et il y en a quatre – a 144 mètres. »

16 juillet 1936

« Faut-il ou ne faut-il pas peindre les horreurs de la guerre ? Par décence devant l’horreur, ce serait non ! Car c’est atroce. Mais il faudrait alors brûler les Rubens, les scènes de Torture – et les Goya et les Manet. Il faudrait mentir à l’histoire et mon Tableau est exact, est un avertissement. »

Reconstitutions

Les premiers jours de la guerre en images.

La parole aux experts

Pour comprendre le contexte historique mais aussi l’approche artistique et picturale.

Comprendre le diorama

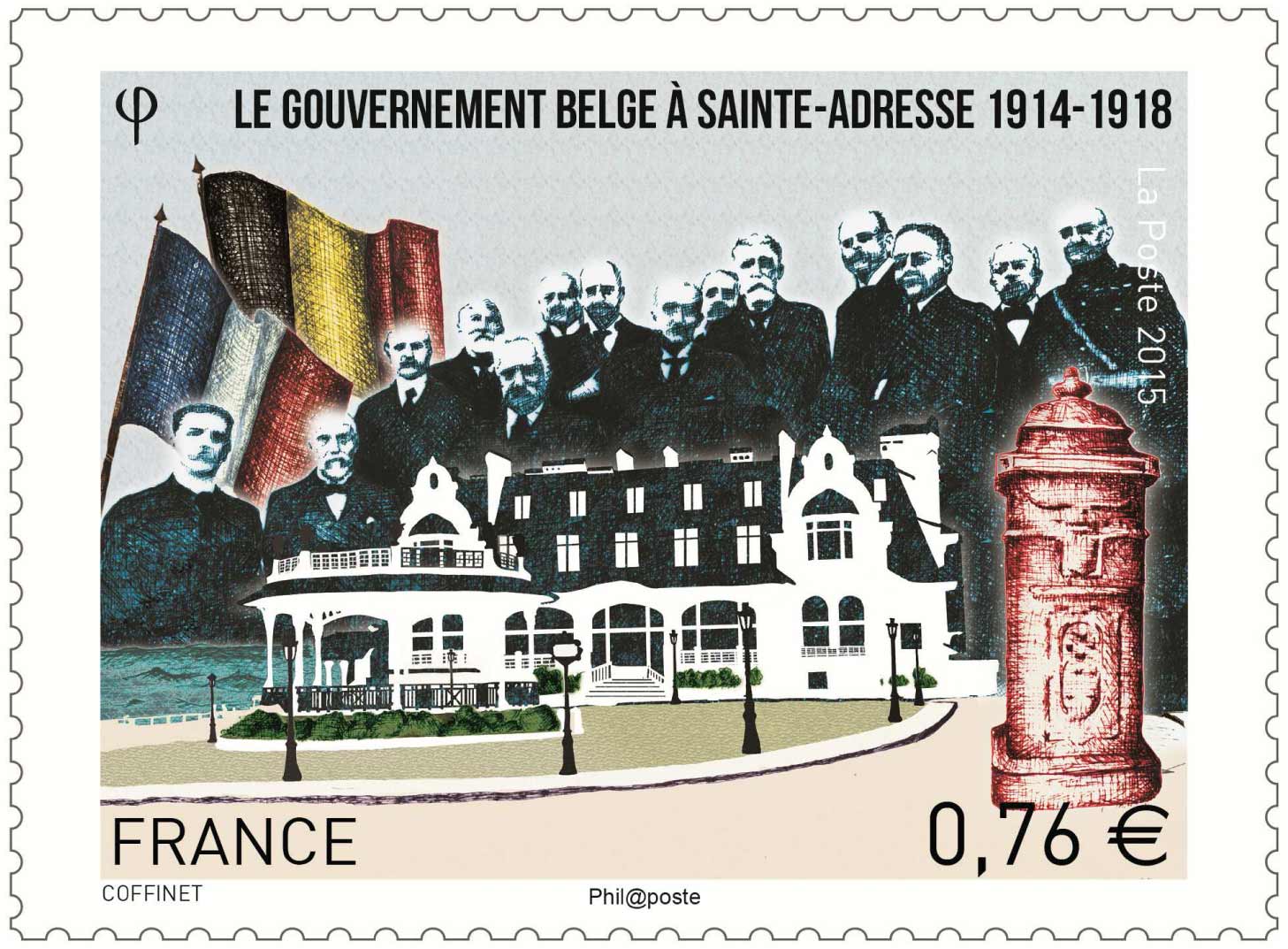

S’il évoque l’agression allemande de la Belgique en 1914, le diorama se veut aussi un cri de l’artiste pour dénoncer le nouveau péril que représente l’Allemagne nazie à l’aube du second conflit mondial.

Les batailles de la Meuse

Le diorama d’Alfred Bastien évoque plusieurs moments-clefs de l’invasion allemande d’août et septembre 1914.

Sont reprises ici les dates importantes de cette période pour mieux comprendre l’enchaînement des évènements.

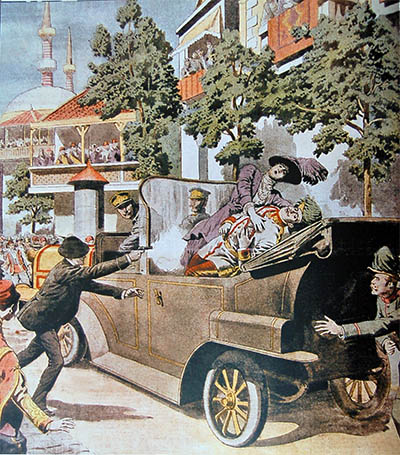

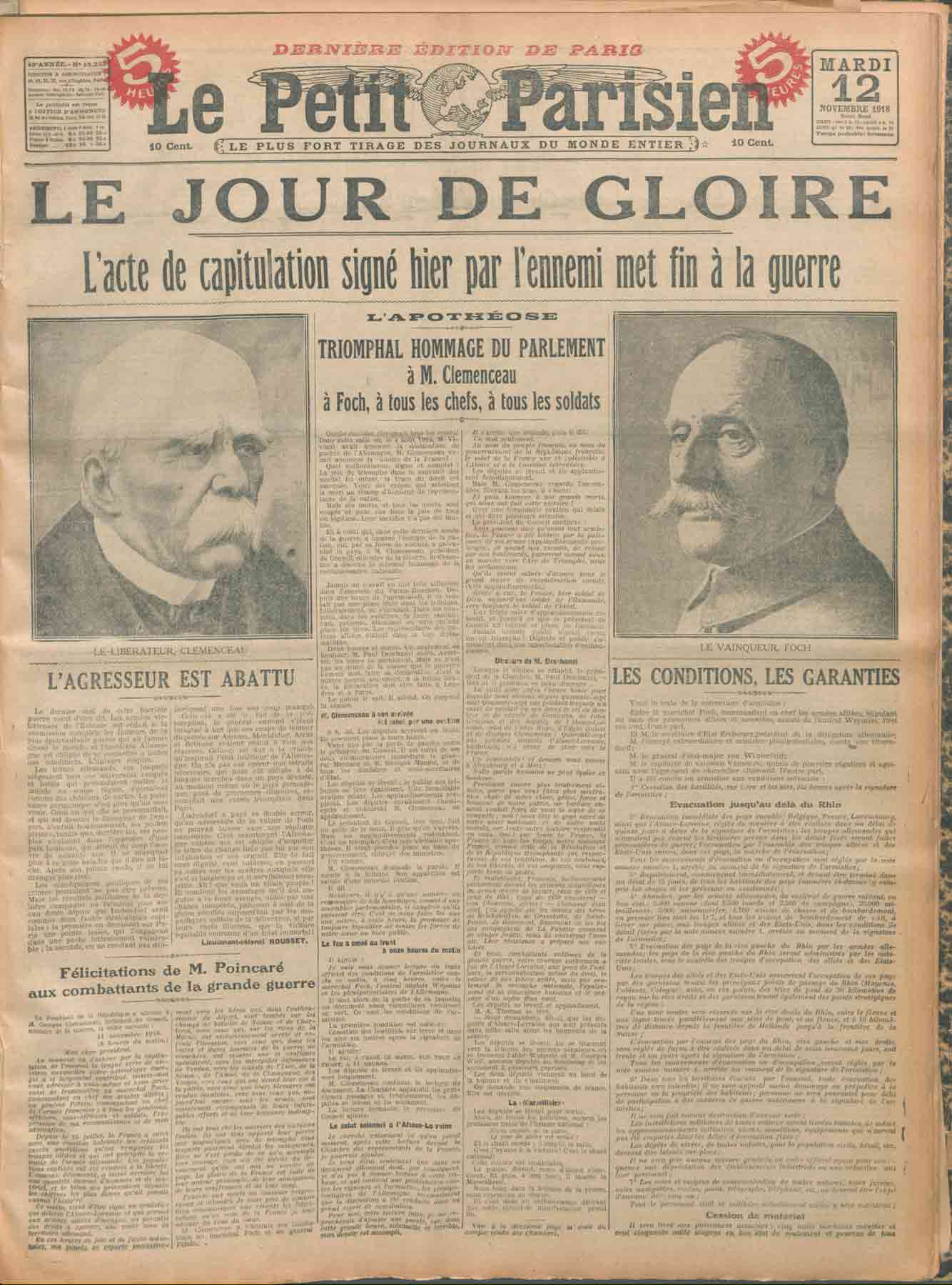

L’assassinat de l’archiduc autrichien François-Ferdinand,

héritier de l'empire austro-hongrois, le 28 juin 1914 par un étudiant nationaliste

serbe met le feu aux poudres.

En quelques semaines, le jeu des alliances, poussé à l’incandescence par les fièvres nationalistes un

peu partout en Europe, aboutit à des déclarations de guerre en

cascade."

Un par un, les pays de la "Triple Alliance" (les empires centraux d’Allemagne et d’Autriche-Hongrie ; l’Italie qui choisit d'abord de rester neutre changera de camp en 1915) s’opposent aux pays de la "Triple Entente" (France, Russie et Royaume-Uni) et à leurs alliés (Belgique, Serbie, Monténégro).

Le 4 août, pour contourner les lignes de défense française, les troupes allemandes entrent en

Belgique.

Théoriquement protégée par sa neutralité, la Belgique fait partie des premières nations

victimes de ce qui deviendra la Grande Guerre.

Le Namurois dans la guerre

En août 1914, l’armée allemande choisit d’envahir la France en passant par la Belgique.

En première ligne, le Namurois conserve le souvenir de cette invasion brutale.

Contribuer au projet

Le Webdocumentaire des Batailles de la Meuse a pour vocation de documenter au mieux cette terrible

période qui a vu l’invasion et l’occupation de la Belgique par l’armée allemande pendant la Première

Guerre mondiale, en particulier les évènements d’août et septembre 1914 décrits sur la toile

d’Alfred BASTIEN.

Pour cela, nous invitons tous ceux qui conserveraient des archives ou documents illustrant ou

expliquant cette période (photos, cartes postales, lettres, documents historiques, etc.) à les

intégrer à ce Webdocumentaire (documents scannés ou en version électronique) comme contributions

complémentaires au projet.

L’idée maîtresse, à travers cette dynamique contributive et participative, est de proposer un

Webdocumentaire enrichi en permanence par les internautes eux-mêmes.

D’avance, nous vous remercions de votre collaboration.

Pour devenir Contributeur au Webdocumentaire des Batailles de la Meuse, vous devez d’abord vous créer un Compte Contributeur en complétant les champs d’information indiqués.

Je dispose de mon Compte Contributeur et je m’identifie pour proposer de nouveaux documents.